These are challenging times for central banks. Inflationary pressures endure. Financial tensions persist. Uncertainty about the outlook for economic activity remains high. In such circumstances, the European Central Bank’s goal remains clear: price stability, in line with our mandate. But, more than ever, we need reliable guides to lead us to this objective.

At the ECB, the money and credit data have proved a crucial signpost. We have long argued that a thorough monetary analysis is central to the determination of interest rate decisions. Not only does such analysis reveal the underlying longer-term inflationary trends in the economy, it also signals the potential emergence of financial imbalances and asset price misalignments that could threaten macroeconomic stability. The close link between monetary developments and evolving imbalances in asset and credit markets implies that monetary analysis can help identify such excesses at an early stage, creating scope for an early preventive policy response. In addition, close monitoring of money and credit data offers an insight into financing conditions, which can strongly influence household and company spending decisions. Each of these elements has proved essential in formulating our response to the financial turmoil seen over recent months.

To illustrate, consider three aspects: the lessons of the past; the experience of the present; and the outlook for the future.

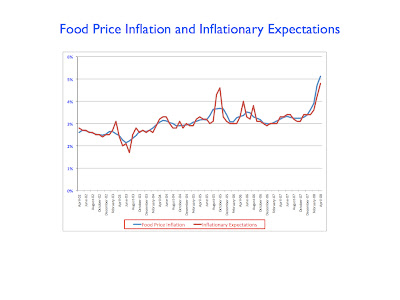

The past: at a time when indicators of real economic developments were – at best – mixed and after an extended period of very low key interest rates, the ECB started to raise rates in December 2005. This decision hinged crucially on the upside risks to price stability identified by the monetary analysis. Subsequent events clearly vindicate this decision. Any further delay in raising rates – which might have followed from neglect of monetary developments – would only have served to exacerbate current inflationary pressures and risked deepening the financial excesses of subsequent years that underlie the recent turmoil. Indeed, given the inflationary pressures apparent in recent data, it appears that the upside risks to price stability associated with the strengthening of underlying monetary growth from late 2004 are now becoming manifest. Some observers even argue that an earlier and more rapid withdrawal of monetary accommodation would have been desirable.

The present: since the emergence of financial tensions in early August 2007, monetary analysis has proved a crucial bulwark for the ECB’s conduct of monetary policy. A close evaluation of the credit data has allowed us to conclude that the availability of bank loans to euro area companies has not been significantly impaired by the financial turmoil thus far. While we continue to monitor developments closely, such evidence has proved an important counter to the gloomy prognosis of “credit crunch” that has driven much of the recent debate on the outlook for the European economy. More fundamentally, the monetary analysis has maintained the necessarily medium-term orientation of monetary policy, at a time when short-term forces threatened to overwhelm it. And it has helped focus our attention on the inflation outlook at longer horizons, over which central banks can exert control and for which they ultimately need to take responsibility.

The future: while the monetary analysis has served us well since the creation of the ECB and particularly in recent months, our experience also points to the need for further development. Enhancing the data, tools and frameworks underpinning the monetary analysis is central to the ECB’s research agenda. Yet the recent financial turmoil also demonstrates that well-established central banking techniques remain valid and important.

Albeit in a somewhat different context, Paul Volcker, former US Federal Reserve chairman, recently emphasised the importance of respecting “certain long embedded central banking principles and practices” in these turbulent times. Such advice is particularly apposite in monetary analysis. We have seen that attempts by banks to shift activity off balance sheet have largely proved to be a chimera, as financial turmoil has forced reintermediation of loans and credit risk. Looking at balance sheet positions of banks, households, corporations and other financial institutions – the “bread and butter” of monetary analysis – should thus again be at the forefront of monetary policy makers’ concerns.

A few days ago, I of course drew pleasure from the Lex column’s recognition of “the ECB’s wisdom” (May 8). As a prudent central banker, I refrain from basking in this unexpected praise. After all, pride precedes a fall. Yet the column sheds important light on my argument. Lex saw the ECB’s “biggest success” as stemming from our “insistence that inflation risks are serious”. While various proximate risks – among others, the rapid increase of commodity prices and the associated potential for second round effects in wage and price setting – are important, it is the analysis of monetary developments that underpins our focus on the outlook for price stability over the medium term that Lex praises. There is no room for complacency in this regard. But, by providing a framework for identifying underlying inflationary trends at an early stage, monetary analysis ensures the ECB remains focused on its mandate, bolstering our credibility and preserving the hard-won goal of price stability.

The writer is a member of the executive board and the governing council of the European Central Bank